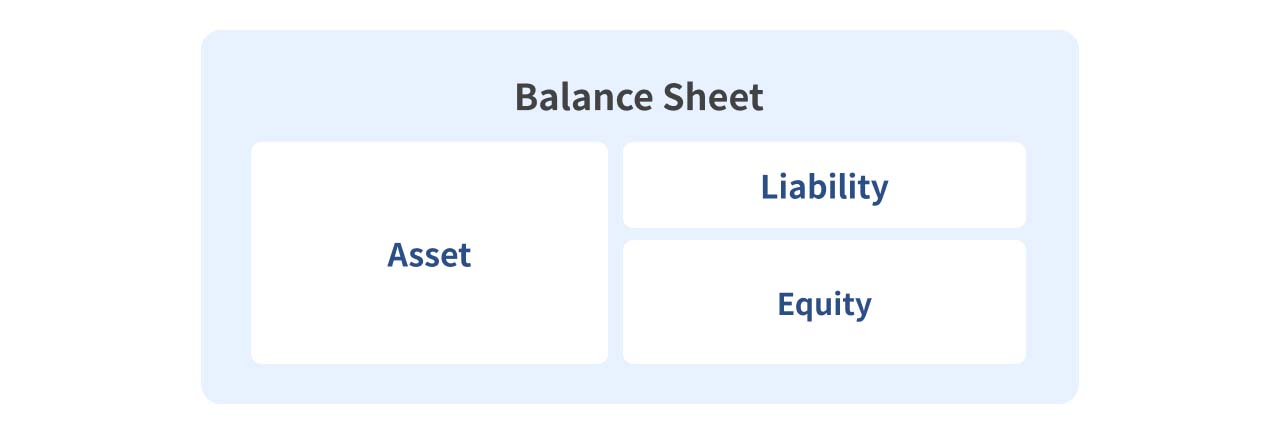

The balance sheet (also known as the statement of financial position) helps us understand a company's financial situation at a specific point in time. In this article, we will explain the different components of the balance sheet.

The Basic Formula of the Balance Sheet

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This formula represents the fundamental accounting equation, which ensures that a company’s resources (assets) are always balanced by its liabilities and equity (the sources of those resources).

The left side of the balance sheet (Assets) answers the question, “How are the company's resources allocated?” while the right side (Liabilities + Equity) answers, “Where do the company's funds come from?”

Below we will be introducing the three sectors in detail respectively.

Classification of Assets

Classified by Liquidity

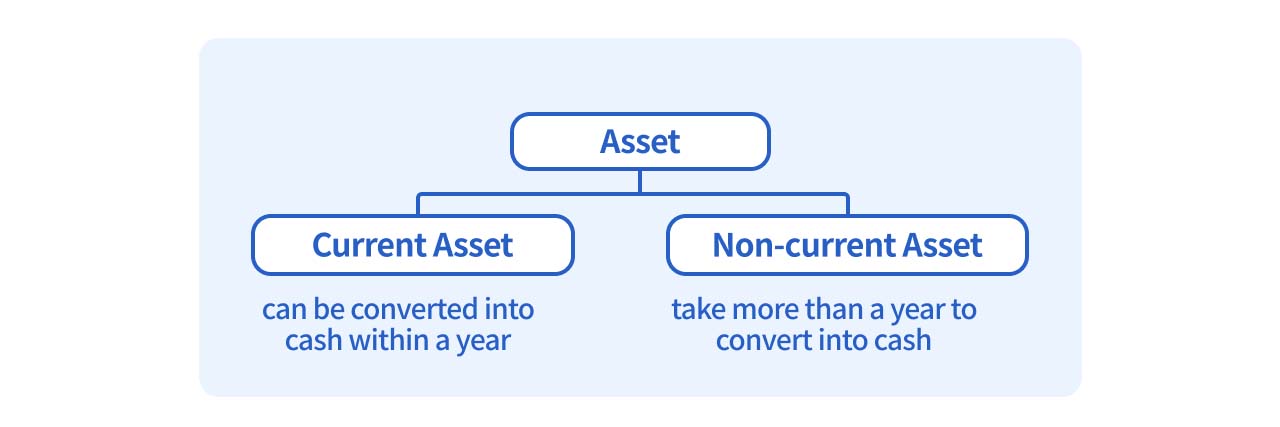

Assets can be categorized into two main types—current assets and non-current assets—depending on their liquidity (i.e., how easily they can be converted into cash).

- Current assets: These are assets that can be converted into cash within a year. Current Assets are crucial for corporations to operate successfully and make timely payments.

- Non-current assets: Assets that take more than a year to convert into cash, often representing long-term investments.

Current Assets

1. Cash and Cash Equivalents

Cash is the most liquid asset, providing the highest flexibility. Cash equivalents refer to items like treasury bills or commercial paper that can be quickly converted into cash (within three months).

A company must maintain adequate cash reserves to handle operational expenses and liabilities. Cash and Cash equivalents are often used to evaluate a company’s ability to payback and invest.

| Low Cash Reserves | High Cash Reserves | |

|---|---|---|

| Investor Concern | The company might face short-term financial risks. | The company may have financial options like investment, expansion, or stock buybacks. |

2. Inventory

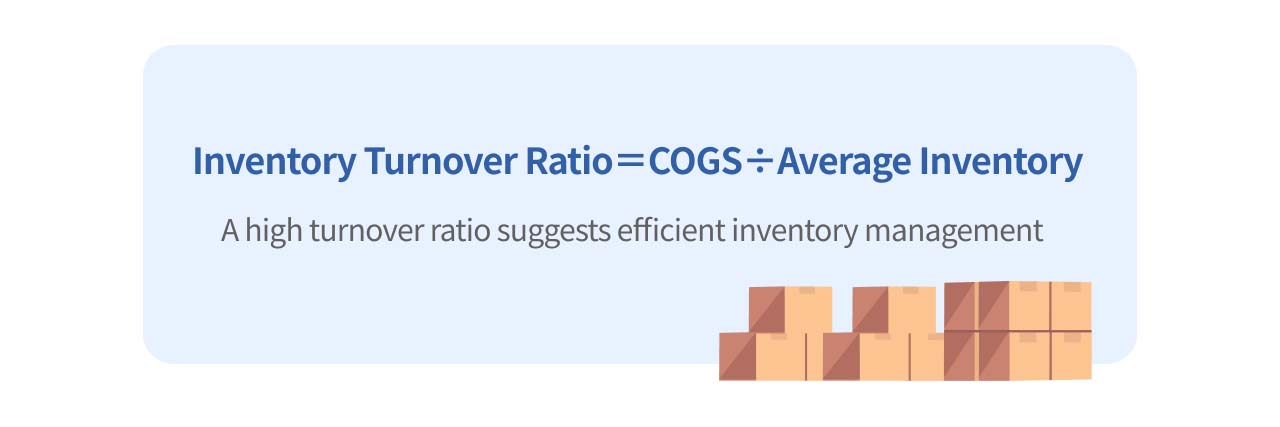

Inventory refers to the stock of goods a company holds for production or sale. By dividing cost of goods sold (COGS) by the average inventory, we get the inventory turnover ratio, which measures how quickly a company sells and replaces its inventory. A high turnover ratio suggests efficient inventory management but might also indicate a risk of stock shortages.

3. Accounts Receivable

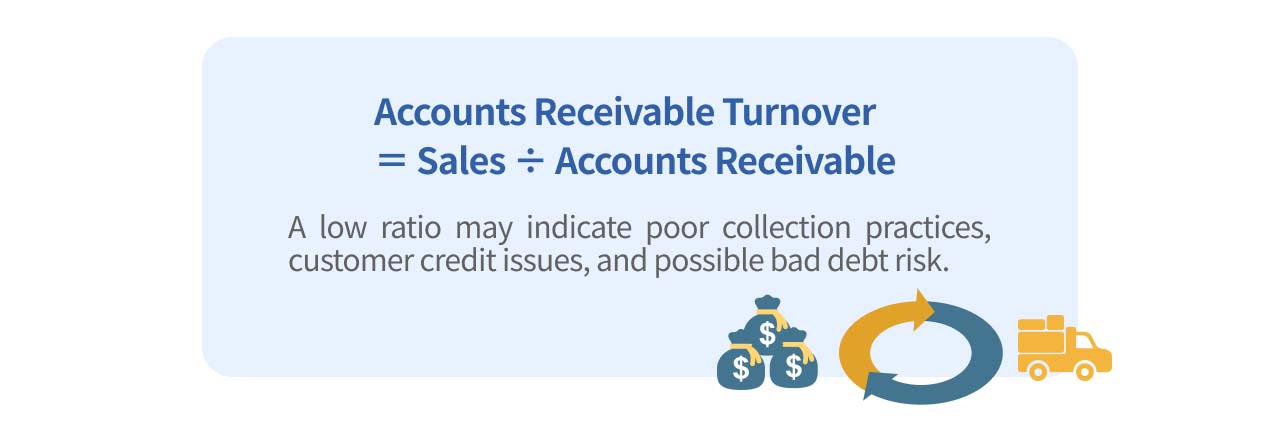

Accounts receivable is money owed to the company for goods or services delivered. The accounts receivable turnover ratio shows how efficiently the company collects payments. A low ratio may indicate poor collection practices, customer credit issues, and possible bad debt risk.

Non-current Assets

1. Fixed Assets

In accounting terms, fixed assets refer to "tangible assets that a business holds for the purpose of producing goods, providing services, leasing to others, or for administrative use, with an expected useful life of more than one year." The most common examples are property, plant, and equipment (PPE), which include machinery, buildings, and vehicles. A key characteristic of these assets is that their depreciation is calculated in various ways to account for wear and tear or aging, leading to a gradual reduction in their value as they approach the end of their useful life.

2. Intangible Assets

Intangible assets, also known as non-physical assets, refer to "assets that cannot be physically touched." These can further be categorized based on identifiability (identifiable):

- Identifiable: Assets that can be separated and sold, such as intellectual property like patents and trademarks. While they may not have a clear price, they can still be transferred.

- Unidentifiable: Assets that cannot be separated, such as goodwill. Goodwill is defined as the premium paid over the value of another company's assets during an acquisition, which includes factors like brand reputation and strong internal and external business relationships.

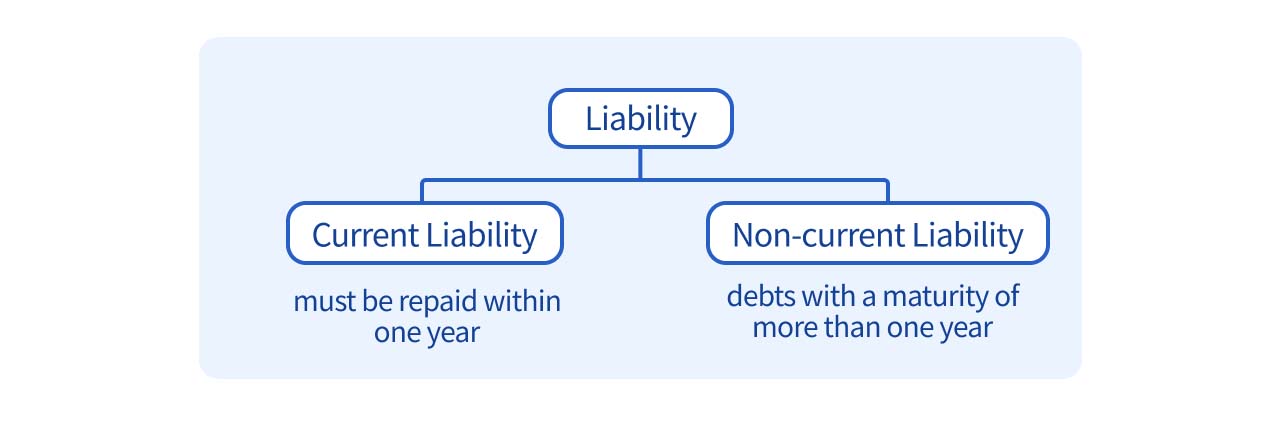

After introducing assets, it's time to move on to the topic of "liabilities." Liabilities, simply put, are all the obligations a company must repay. For various reasons, such as maintaining operations or expanding business scale, companies often need to borrow money, thus becoming debtors. Debtors are obligated to repay, and these obligations are recorded on the liabilities side of the balance sheet. Investors can assess a company's overall debt situation by looking at the total liabilities on the balance sheet.

Classification of Liabilities

Classified by Liquidity

Generally, just like assets, liabilities can also be categorized by liquidity into current liabilities and non-current liabilities. The main difference between the two lies in the length of the debt maturity. Current liabilities refer to debts that must be repaid within one year, while non-current liabilities are debts with a maturity of more than one year.

Current Liabilities

Current liabilities are typically used to support a company’s short-term daily operations, with key items including accounts payable, short-term borrowings, and other similar entries.

1. Accounts Payable

Accounts payable refers to the money a company owes to suppliers for raw materials or other equipment it has purchased but not yet paid for. Simply put, it can be viewed as the counterpart of accounts receivable, which we previously discussed under assets. A higher accounts payable balance might indicate that a company has strong bargaining power, allowing it to acquire goods before making payments. However, the company must carefully assess its ability to manage short-term liabilities. Excessively high accounts payable may put pressure on the company's short-term cash flow.

2. Short-Term Borrowings

Short-term borrowings refer to loans a company takes out for immediate funding needs during its regular operations, primarily to address liquidity issues. A common reason for such borrowings is to increase the company’s flexibility in managing short-term finances. For instance, companies may need short-term loans to support operations during off-peak sales seasons or when large payments are delayed.

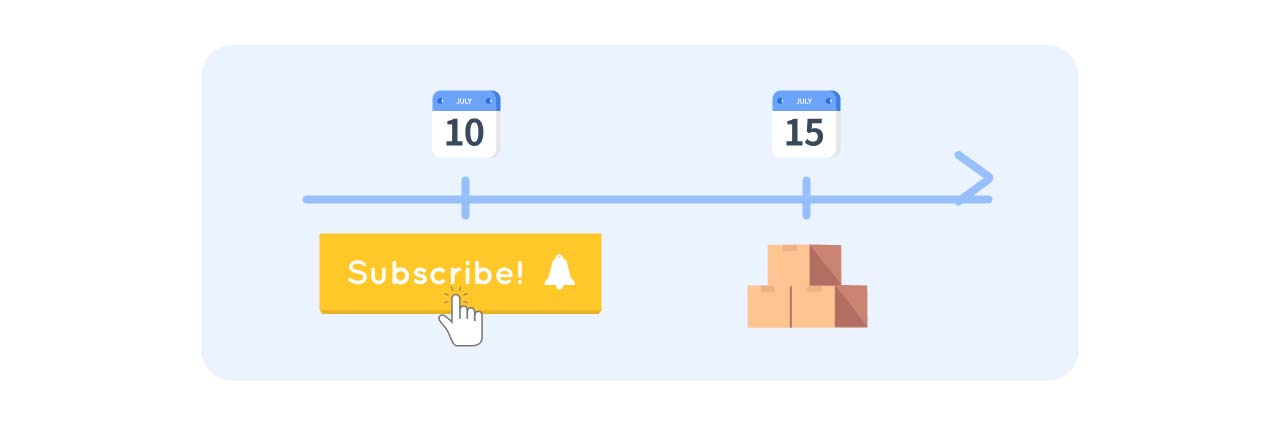

3. Unearned Revenue (Prepayments)

Unearned revenue refers to income a company receives in advance, typically when a customer makes a payment before the company has delivered the goods or services. For example, when a company signs a contract with a customer and the customer prepays (such as for an annual subscription), the unearned revenue (contract liability) will appear on the liabilities side of the balance sheet until the company fulfills its obligations under the contract.

Measuring Short-term Solvency with the Current Ratio

Current Ratio = Current Assets ÷ Current Liabilities

When assessing a company's debt repayment ability, the current ratio is one of the commonly used financial ratios. The current ratio measures the relationship between a company's current assets and current liabilities. Generally, we want to see the current ratio maintained at a relatively healthy level over the long term. As investors, we can quickly compare a company's current ratio with its industry peers (to identify different trends across industries) and also closely examine the composition of short-term liabilities. If there is a large proportion of borrowing (such as short-term borrowings or long-term debt maturing within a year), it is important to carefully evaluate the company's financial risk in meeting its short-term obligations.

Non-current Liabilities

Non-current liabilities are defined as all company debts that are not classified as current liabilities, with repayment periods exceeding one year, and are often referred to as long-term debt. Long-term debt is frequently used as a stable source of financing for acquiring long-term assets. Efficient companies can use long-term debt to leverage their finances, enabling them to expand investments or increase production capacity, thereby enhancing future business competitiveness. Non-current liabilities generally include long-term borrowings, bonds payable, or long-term (non-current) lease liabilities.

A company's financial leverage is one of the key factors that investors consider when making investment decisions. However, the level of financial leverage is not inherently good or bad, as it depends on the company’s management style and industry characteristics. The critical point for investors is whether the company can efficiently use financial leverage to strengthen its operational advantages.

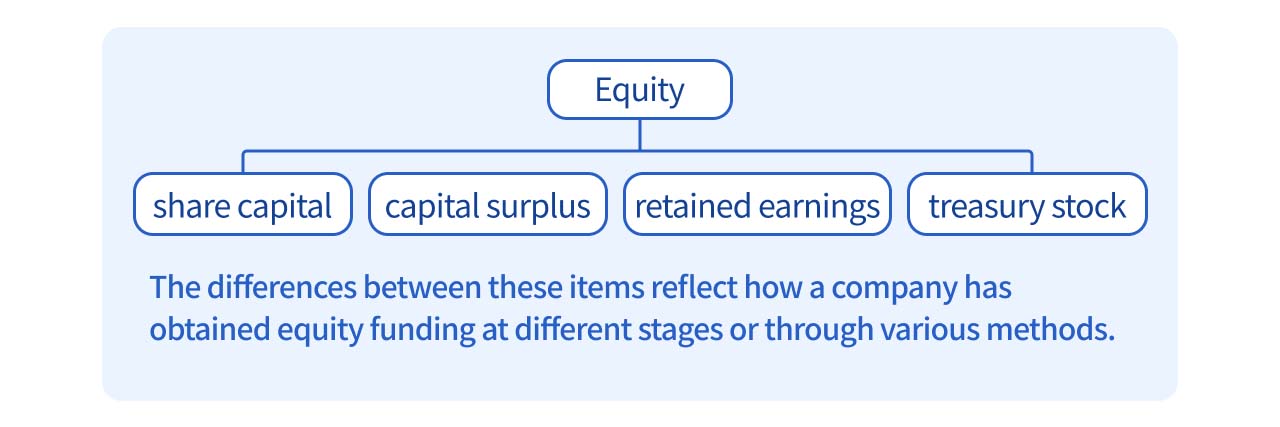

Finally, we’ll cover equity, the final component of the balance sheet.

Components of Equity

Compared to assets and liabilities, the concept of equity might be less familiar. Simply put, equity represents the value of the company that is owned by its shareholders, which also reflects the company’s current book value. To better understand the meaning of equity, we can start by looking at the composition of the balance sheet.

Equity can generally be divided into "share capital," "capital surplus," "retained earnings," and "treasury stock." The differences between these items reflect how a company has obtained equity funding at different stages or through various methods. Let’s now take a closer look at each of these components.

1. Share Capital

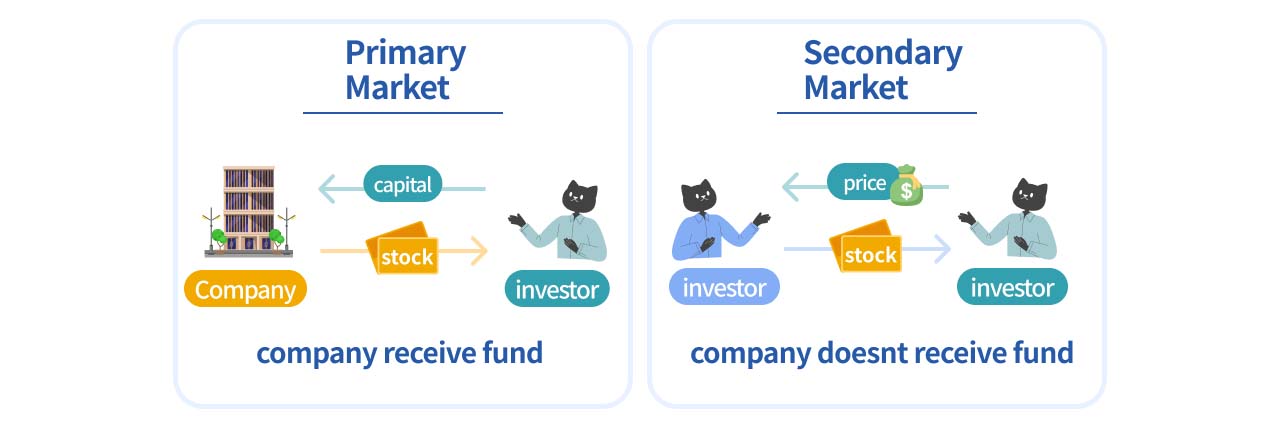

Share capital refers to the funds a company raises by issuing shares. A company can issue shares in the primary market to raise capital, which can then be used to expand production capacity or enter new markets, ultimately enhancing its future competitiveness.

The primary market refers to the market where securities are traded for the first time. When a company needs to raise funds, it can use intermediaries, such as investment banks, to underwrite and find investors with capital to invest. What we typically see in trading apps, where prices fluctuate by the second, is called the secondary market, which differs from the primary market discussed above.

Investors who purchase shares in the primary market can later resell them in the secondary market (subject to restrictions or protective covenants). However, when investors freely buy and sell shares in the secondary market at mutually agreed prices, the cash flow remains between investors and is no longer related to the company’s share capital.

We can further calculate the total share capital by multiplying the "par value" of each share by the "number of outstanding shares." In Taiwan, the par value of issued shares is generally set at NT$10 per share.

Share Capital = Par Value X Outstanding Shares

2. Capital Surplus (Share Premium)

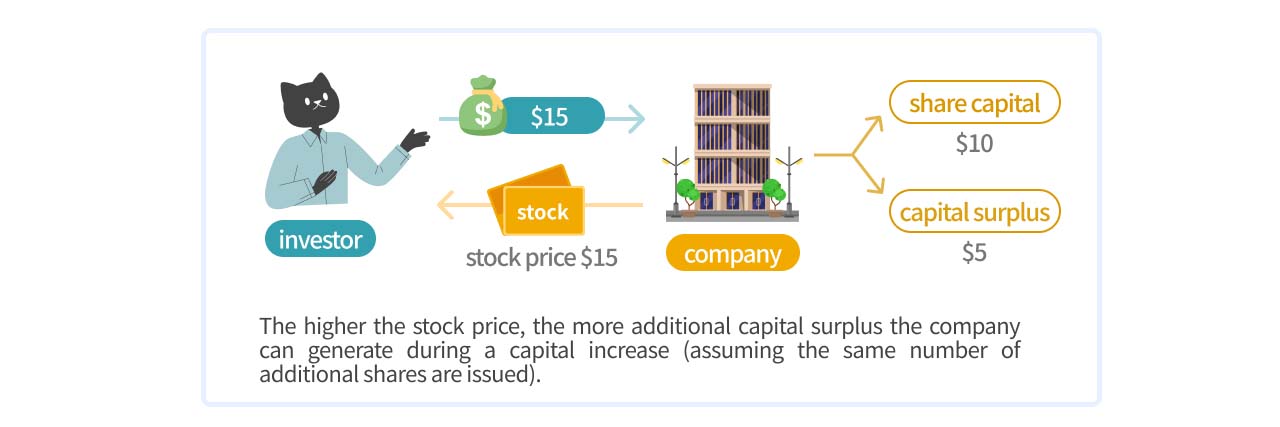

From the introduction above, we can see that the "market price" of stocks traded in the secondary market does not have a direct connection with the size of a company's share capital. When the stock price is higher, investors will need to pay more to purchase shares during a capital increase. You may be wondering how the excess amount is handled, as it would not be included in the share capital. This brings us to the concept of capital surplus.

Below is a simple example to illustrate: assuming a par value of NT$10 per share, if an investor purchases the stock for NT$15, the NT$10 portion corresponding to the par value will still be accounted for as share capital. However, the extra NT$5 per share will be recorded under capital surplus. The higher the stock price, the more capital surplus the company can generate during a capital increase (assuming the same number of additional shares are issued).

3. Retained Earnings

In the article Financial Report 101: Introduction to the Income Statement, we bring up the idea of net income. After a company deducts various direct and indirect costs from its revenue and pays its taxes, the remaining amount is the net income for that year. After closing the books for the year, the net income is transferred to the balance sheet as part of the company's retained earnings.

Retained earnings represent all profits the company has generated since its inception and is an item that capitalizes those earnings into the company’s assets. According to current regulations, retained earnings can be classified into:

- Legal reserve: Legally mandated to be retained.

- Special reserve: Set aside by the company as stipulated in its bylaws, usually for specific purposes.

- Undistributed earnings: Freely available for reinvestment or dividend distribution.

4. Treasury Stock

When a company has excess cash, it may consider repurchasing its own issued shares to reduce the number of outstanding shares. Remember the earnings per share (EPS) metric we discussed in Financial Report 101: Introduction to Earnings Per Share (EPS)? When the number of outstanding shares decreases due to stock buybacks, the EPS can increase even if total earnings remain unchanged. Treasury shares usually follow one of three outcomes: they can be distributed to internal employees, reissued at a later time, or the company may choose to cancel them.

These are the common components of shareholders' equity! In practice, management has a wide variety of strategies for utilizing equity items, many of which are important considerations for investors.

For people who are interested in more financial statements introduction, check out our articles on:

Financial Report 101: Introduction to the Income Statement

Financial Report 101: Introduction to the Cash Flow Statement