Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, commonly known as “Section 232,” authorizes the U.S. president, upon completion of an investigation by the Department of Commerce, to impose tariffs or restrict imports if certain imported goods are deemed to pose a threat to national security.

In the past, this provision mainly applied to strategic base industries such as steel and aluminum. Recently, however, the U.S. government has broadened the definition of national security, extending its focus to semiconductors. It is now considering imposing tariffs of up to 300% on these products. The goal is to strengthen U.S. domestic manufacturing, reduce reliance on foreign supply chains, and ensure leadership in critical technology sectors.

Below we will be exploring through how this move will reshape the survival model of industries in the market.

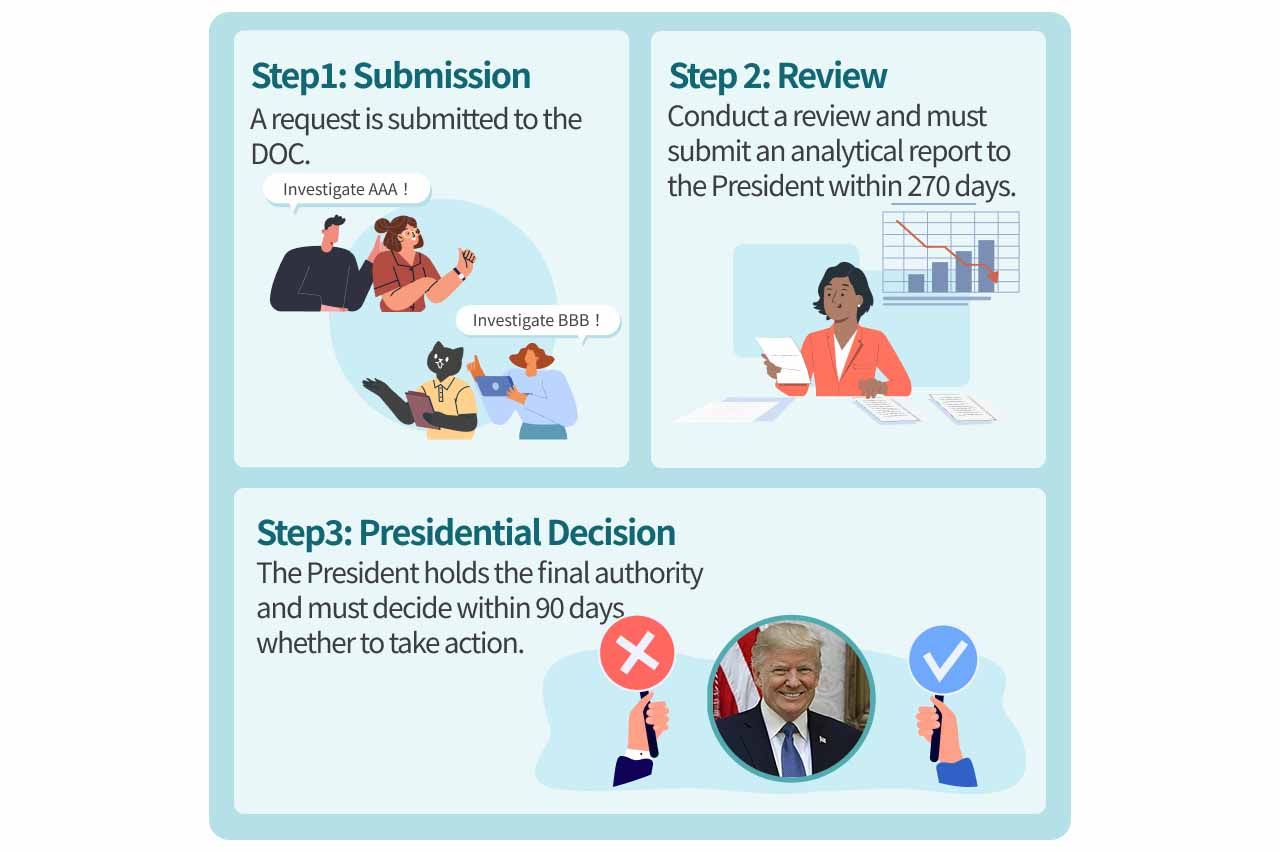

Section 232 Investigation Process

The U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) is responsible for conducting the investigation.

Process:

- A request for investigation can be filed with the DOC by U.S. companies, labor unions, or government agencies. The DOC may also initiate an investigation on its own authority.

- The DOC evaluates the national security implications of the imports, solicits public input from industry, civic groups, academia, and government entities, and must submit a report to the president within 270 days.

- The president has the final say and must decide within 90 days whether to take action, which may include imposing tariffs or import restrictions.

Comparing Trade Provisions

In U.S. trade policy, Sections 201, 232, and 301 are commonly used to restrict imports or impose tariffs, though their legal bases and criteria differ. Conceptually, Section 232 is unique because its activation is based on national security considerations, which often brings more political implications compared to the others.

| ⭐ Section 232 | Section 201 | Section 301 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Basis | Trade Expansion Act of 1962 | Trade Act of 1974 | Trade Act of 1974 |

| Trigger | Threat to national security | Injury to U.S. industry from imports | Unfair trade practices |

| Authority | U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) | U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) | U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) |

| Measures | Tariffs, quotas, import restrictions, non-trade actions (e.g. R&D subsidies) | Tariffs, quotas, import restrictions | Tariffs, quotas, retaliatory measures |

| Cases | Steel, aluminum, autos | Safeguard tariffs on washing machines, solar cells & modules | U.S.–China trade war |

Current Investigations and Progress

Tariffs are already imposed on three major categories: steel & aluminum, autos & parts, and copper.

- Steel & aluminum and derivatives: As of March 2025, all exemptions were removed. In June, tariffs were raised from 25% to 50%, and in August the scope expanded to 407 additional derivative products. The UK maintains a lower 25% tariff.

- Automobiles & parts: Building on a 2018 investigation, Trump imposed a 25% tariff on imported vehicles in April 2025, later extending it in May to auto parts. A tax credit system allows automakers to offset tariffs based on their U.S. production scale.

- Copper: Effective August 1, a 50% tariff applies to all semi-finished copper products and derivatives with high copper content, highlighting the U.S. focus on strategic raw materials.

Since Trump’s second term began, nine new Section 232 investigations have been launched, covering lumber, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, critical minerals, drones, commercial aircraft, and polysilicon. Results remain pending. Proposed tariffs include up to 250% on pharmaceuticals and up to 300% on semiconductors, with exemptions for companies building or investing in U.S. facilities.

Section 232 Investigation List

| Start Date | Public Comment Deadline | Scope | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 3/10/2025 | 4/1/2025 | Semi-finished copper products, high-copper-content derivatives | Trump signed an executive order: 50% tariff from 8/1, excluding raw copper (ores, concentrates) and scrap |

| Lumber | 3/10/2025 | 4/1/2025 | Unprocessed wood, panels, derivatives (paper, furniture, cabinets) | Ongoing |

| Semiconductors & equipment | 4/1/2025 | 5/7/2025 | Wafers, legacy chips, advanced chips, microelectronics, equipment parts; downstream products with chips | Trump proposed tariffs up to 300%; exemptions for U.S.-based investments |

| Pharmaceuticals | 4/1/2025 | 5/7/2025 | Finished drugs, medical countermeasures, active ingredients, related derivatives | Trump stated tariffs may rise gradually to 250% over 1–1.5 years |

| Critical minerals & derivatives | 4/22/2025 | 5/16/2025 | Minerals (cobalt, nickel, rare earths, uranium), processed products, derivatives (chips, permanent magnets, EVs) | Ongoing |

| Trucks | 4/22/2025 | 5/16/2025 | Medium/heavy trucks, parts, derivatives | Ongoing |

| Commercial aircraft & jet engines | 5/1/2025 | 6/3/2025 | Complete aircraft, jet engines, power units, major components | Ongoing |

| Drones (UAS) & parts | 7/1/2025 | 8/6/2025 | Civilian & commercial drones (consumer to industrial), key systems (imaging, sensors, comms, flight control) | Ongoing |

| Polysilicon & derivatives | 7/1/2025 | 8/6/2025 | Polysilicon, semiconductor wafers, solar cells & modules | Ongoing |

Industry Impact Analysis

| U.S. Import Dependence | Key Import Sources | Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steel & Aluminum | ~25% steel import reliance; ~50% aluminum, higher for specialized aerospace/defense-grade aluminum | Steel: Canada, Mexico, Brazil, China, TaiwanAluminum: Canada, UAE, Mexico, South Korea, China | Higher import costs benefit U.S. producers but hurt downstream users (autos, machinery, appliances). Canada is most affected due to its heavy reliance on U.S. |

| Autos & parts | Nearly 50% of new cars and 60% of parts imported | Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Germany | Mexico is most affected due to high GDP exposure. USMCA may offset some impact. U.S. costs for cars and parts will rise, boosting local output but raising consumer prices |

| Copper | ~50% import reliance | Chile, Canada | Canada most impacted. Chile exports mostly refined copper (cathodes), exempt from tariffs |

| Lumber | ~30% import reliance | Canada | Tariffs may neutralize Canadian subsidies but raise U.S. construction costs |

| Semiconductors & equipment | $200+ billion trade deficit in 2024 | China, Taiwan, Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia | Reshapes supply chains, drives more U.S. investment in fabs. U.S. firms like Qualcomm and Nvidia still reliant on overseas foundries, raising costs |

| Pharmaceuticals | 80% of generics and 50% of patented drugs imported | Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, Singapore, China, India | EU tariffs cut to 15%, so impact limited. U.S. provides 1-year transition, but high tariffs may raise end-user costs |

| Critical minerals & derivatives | 12 minerals 100% import-reliant; 28 minerals >50% reliant | South Africa, Canada, China | China dominates rare earths & critical minerals. U.S. is working with MP Materials and allies, but faces near-term supply shortages |

| Trucks | ~50% import reliance | Mexico, Canada | Boosts U.S. domestic manufacturing but risks short-term supply disruptions |

| Aircraft & jet engines | $33B trade deficit in 2024 | EU, Canada, UK | Raises production costs, disrupts aerospace supply chains |

| Drones (UAS) | DJI holds over 50% of U.S. market | China | Reduces reliance on Chinese dominance, supports U.S. firms like Red Cat Holdings (RCAT) and its Teal Drones unit |

| Polysilicon & derivatives | China dominates global manufacturing | China, Southeast Asia | Disrupts low-cost supply chains, benefits U.S. firms like REC Silicon and First Solar (FSLR) |

Conclusion

Trump’s use of Section 232 marks a sharp shift from Biden’s trade strategy. While Biden emphasized subsidies, alliances, and infrastructure to strengthen U.S. manufacturing, Trump is leaning heavily on tariffs to directly reshape import dependence. His approach pressures foreign companies to build or invest in U.S. facilities in exchange for market access.

This strategy may boost domestic capacity and jobs in the short term but also risks higher consumer prices, supply chain disruptions, and retaliation from trade partners. From steel and drugs to critical minerals and drones, Section 232 shows how “national security” is now a broad framework in U.S. trade policy.

For industries, the challenge ahead is to find a new balance between “Made in America” and global competitiveness—managing policy pressures while ensuring long-term efficiency and growth.